Noisy-channel coding theorem

Here is my second attempt to understand the proof for the channel coding theorem. My initial exposure to this concept was through Professor Amos Lapidoth’s lecture in Information Theory I. His presentation, though concise, was packed with ingenious methods that were challenging to fully comprehend at time. To better understand it, I shall employ the Feynman technique - explaining the concept to someone else.

1. Communication through a noisy medium

Imagine Bob’s wife, Alice, is traveling the universe for her company annual trip. She wants to send her lovely husband some gorgious photos she’ve taken during the last couples of days. From Alice’s space ship, these photos are first encoded as binary strings (e.g. \(00101101..\)), then converted into radio waves and finally emitted to Bob’s computer on Earth.

However, every interplanetary species know how deadly and quirky the space is, and signals travel through this medium is of no exception. Due to cosmic radiation, the sent bit has a probability \(p\in [0,1]\) of being flipped; \(0\) is received as \(1\) at Bob’s computer given some chance \(p>0\) for instance.

To circumvent such situation, the ship can send the same bit multiple times just to be sure that the receiver can recover the message faithfully. For example, Alice can instead send \(010\) as \(000111000\) (each bit is duplicated three times). The encoder at Alice’s spaceship would then follow the mapping:

\[\begin{align} 0 &\rightarrow 000\\ 1 &\rightarrow 111 \end{align}\]On Earth, Bob can leverage a voting scheme to decode the message, say, for every block of 3 bits, decodes it as the majority bit in that block (e.g. \(011 \rightarrow 1\)).

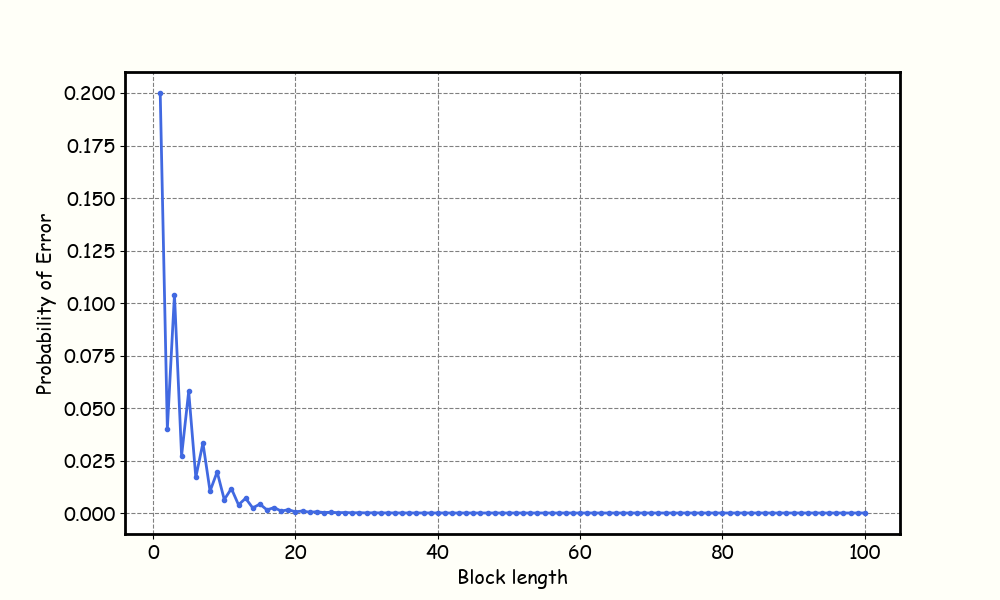

To be more concrete, let’s assume \(p=0.2\). Before, the probability of incorrectly receiving a bit \(P_e\), say bit \(0\) is received and decoded as \(1\), equals to \(0.2\). Now, with the redundant bits introduced, the error happens when \(000\) is received as one of \(\{011, 101, 110, 111\}\) (Bob will decode it as a \(1\)), and this event occurs with probability \(P_e \approx 0.104\)! It seems like the probability of error \(P_e\) will vanish as we keep sending the same bit for a large number of times. Wonderful right? However, the reduction in \(P_e\) would come with a cost!

Every time the space ship sends a bit through the radio channel, this service charges Alice some amount of money. In case the encoder duplicates a bit \(K\) times, the rate of communication would then be \(R=\frac{1}{K}\) bits per channel use. To send a single bit reliably, the ship emits \(K\) times the radio signal to transmit it to Earth. From the previous, we speculate that only when \(R \rightarrow 0\) then \(P_e\rightarrow 0\). Bad news for the family’s bank account!

But the couple have to worry no more, Claude Shannon dropped a phenomenal paper in 1948 which states that \(\forall \varepsilon>0\), there exists an encoder-decoder pair that allows us to make \(P_e < \varepsilon\) without the need to drive \(R\rightarrow 0\). In plain words, you can make the probablity of error arbitrarily small and still having a reasonable communication rate.

2. Noisy-channel coding theorem

Formally, the basic scheme consists of a set of messages \(\mathcal{M}\), an encoder \(f: \mathcal{M} \rightarrow \mathcal{X}^n\) with \(n\) be the block length, and a decoder \(\phi: \mathcal{Y}^n \rightarrow \mathcal{M} \cup \{?\}\). The symbol \(?\) denotes the failure case when the decoder doesn’t know the original message. The communication rate is \(R=\frac{\log |\mathcal{M}|}{n}\) bits per channel use, assume the messages are drawn uniformly. We can index \(\mathcal{M}\) by \(\{1,\dots, \lfloor 2^{nR} \rfloor\}\). Finally, the noisy channel \(W(\mathcal{Y}|\mathcal{X})\) is memoryless and assumed to be fixed in this setting.

Definition 1: The probability of error associated with message \(m\) is denoted by \(\lambda_m\). Verbosely,

\[\begin{align} \lambda_m &= \sum_{\mathbf{y} \in\mathcal{Y}^n | \phi(\mathbf{y}) \neq m} P(Y = \mathbf{y} | X = \mathbf{x}(m))\\ &= \sum_{\mathbf{y} \in\mathcal{Y}^n | \phi(\mathbf{y}) \neq m} \prod_{i=1}^n W(y_i | x_i(m)) &\text{(Channel is memoryless)} \end{align}\]Next, we define \(\lambda_\max = \underset{m\in \mathcal{M}}{\max} \lambda_m\), the maximum chance of getting an error considering all messages. The average error chance is \(P_e^{(n)} = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{M}|} \sum_{m\in \mathcal{M}} \lambda_m\).

Definition 2. Rate \(R\) is achievable if there exists a sequence of encoder-decoder pairs \(\{f, \phi\}_n\) such that \(\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} \lambda_\max = 0\).

Definition 3: The capacity of a channel, denoted \(C\), is the supremum of all achievable rates. Furthermore, we define \(C^{(I)} = \underset{Q\in P_\mathcal{X}}{\max} I(Q, W)\), where \(Q\) is a probability distribution for input symbols in \(\mathcal{X}\) and \(I(\cdot;\cdot)\) is the mutual information between two distributions.

Shannon’s noisy-channel coding theorem: \[ C = C^{(I)} \]

This theorem consists of two parts which we shall prove consequently:

- Converse part: If \(R > C^{(I)}\), then \(R\) is not achievable.

- Direct part: If \(R < C^{(I)}\), then \(R\) is achievable.

2.1 Converse part

A contrapositive statement for the converse says that if you give me a wonderful encoder-decoder pair whose rate \(R\) is achievable (e.g. \(\lambda_\max \rightarrow 0\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\)), then \(R \leq C^{(I)}\). Next, I would like to introduce the Fano’s inequality which is necessary for the proof later:

Fano’s inequality:

\[\begin{align} H(M|Y) &\leq H(P_e) + P_e\log(|\mathcal{M}|-1)\\ &\leq 1 + P_e\log|\mathcal{M}| \end{align}\]Where \(P_e=P(\hat{M} \neq M)\) with \(\hat{M}=\phi(Y)\in\mathcal{M}\). We have \(H(P_e)\leq 1\) because \(P_e\) is a Bernoulli distribution and the maximum entropy of a binary random variable is \(1\) bit. The proof for this inequality is rather a trivial algebraic manipulation, for curious readers you can refer to Elements of Information Theory by Thomas & Cover.

Proof of the converse part:

\[\begin{align} nR = \log |\mathcal{M}| = H(M) &= I(M; Y^n) + H(M|Y^n)\\ &\leq I(M; Y^n) + 1 + P_e^{(n)}nR &\text{(Fano's inequality)} \end{align}\]Dividing \(n\) both sides,

\[R \leq \frac{1}{n} I(M; Y^n) + \frac{1}{n} + P_e^{(n)}R\]Given that \(R\) is achievable, we have \(P_e^{(n)}\rightarrow 0\). Also, \(\frac{1}{n}\rightarrow 0\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\). The remain work is to bound \(\frac{1}{n} I(M; Y^n)\):

\[\begin{align} I(M; Y^n) &\leq I(X^n; Y^n) &\text{(Data Processing Ineq.)}\\ &= H(Y^n) - H(Y^n|X^n) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n H(Y_i|Y^{i-1}) - H(Y_i|Y^{i-1}, X^n) &\text{(Chain rule)}\\ &\leq \sum_{i=1}^n H(Y_i) - H(Y_i|X_i) &\text{(Channel is memoryless)}\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n I(X_i; Y_i)\\ &\leq n \underset{Q\in P_\mathcal{X}}{\max} I(Q; W) = n C^{(I)} \end{align}\]Hence, \(\frac{1}{n} I(M; Y^n) \leq C^{(I)} \Rightarrow R \leq C^{(I)}\), completing the proof.

2.2 Direct part

We would need several key ingredients for the actual proof of the direct part.

Joint Weak Typicality. Given a joint probability \(P_{XY}\) and a tolerance $\epsilon$, and two sequences \(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y}\) that satisfy the following conditions:

- \(\mathbf{x}\) is weakly typical, e.g. \(2^{-n(H(P_X)+\epsilon)} < \prod_{i=0}^n P_X(x_i) < 2^{-n(H(P_X)-\epsilon)}\).

- \(\mathbf{y}\) is weakly typical, e.g. \(2^{-n(H(P_Y)+\epsilon)} < \prod_{i=0}^n P_Y(y_i) < 2^{-n(H(P_Y)-\epsilon)}\).

Then, the pair \((\mathbf{x, y})\) is weakly typical if \(2^{-n(H(P_{XY})+\epsilon)} < \prod_{i=0}^n P_{XY}(x_i, y_i) < 2^{-n(H(P_{XY})-\epsilon)}\). We denotes such event as \((\mathbf{x,y}) \in \mathcal{A}_\epsilon^{(n)}(P_{XY})\). A jointly typical pair of sequences has some properties that will be needed for the main proof:

- If the elements of \((\mathbf{x,y})=\{(x_i,y_i)\}_{i=1}^n\) are drawn IID from \(P_{XY}\), then for any \(\delta>0\) there exists \(N(\delta)\) so that \(\forall n>N(\delta)\) we have \(\text{Pr}((\mathbf{x,y}) \notin \mathcal{A}_\epsilon^{(n)}(P_{XY})) \leq \delta\).

- If \(\mathbf{x}=\{x_i\}_{i=1}^n\) and \(\mathbf{y}=\{y_i\}_{i=1}^n\) are drawn IID from \(P_X\) and \(P_Y\) respectively, then the chance that the pair of sequences \((\mathbf{x,y})\) is jointly typical is very unlikely:

Proof of the direct part:

Let us fix the input symbols distribution \(Q \in P_X\). We would like to prove that for any rate \(R < I(Q, W)\), \(R\) is achievable. If we can prove this previous statement, the same thing holds when \(Q\) is the capacity-achieving input distribution and hence the proof for \(R < C^{(I)}\) follows naturally.

To decode the messages, we shall use something called jointly typical decoding. For a given output sequence \(Y^n\) from the channel, we check for the existance of a message \(m\) whose code \(X^n(m)\) is jointly typical with \(Y^n\), e.g. whether \((X^n,Y^n) \in \mathcal{A}^{(n)} (P_{XY})\). If there exists a single \(m\) satisfies this condition, return \(m\). Otherwise, if there is none or multiple such \(m\)’s, we declare error.

Now, consider a random rate-\(R\) blocklength-\(n\) codebook \(\mathcal{C}\). To construct this codebook, the row elements (there are \(n\) of them) in each of the \(2^{nR}\) rows in \(\mathcal{C}\) are drawn IID from \(Q\). The probability of error for message \(m\) associating with this codebook is denoted by \(\lambda_m(\mathcal{C})\). The expected error is then written as \(\bar{\lambda}_m = \mathbb{E}_{P_{\mathcal{C}}}[\lambda_m(\mathcal{C})]\). Similarly, the average error for codebook \(\mathcal{C}\) is \(P_e^{(n)}(\mathcal{C})\) and the expected average error is \(P_e^{(n)}\).

Claim 1: The expected error is independent of the message \(m\), e.g. \(\bar{\lambda}_1 = \dots = \bar{\lambda}_m\).

Proof of claim 1 (non-rigorous): This is due to symmetry!

Follow from claim 1, we can easily see that the expected average error \(P_e^{(n)}=\bar{\lambda}_1\). From now on, we will focus on bounding \(\bar{\lambda}_1\) which turns out to be easy to work with!

Given that \(m=1\) and the fact that we are using jointly typical decoding, let us define \(\varepsilon_i = [(X^n(i), Y^n) \in \mathcal{A}_\epsilon^{(n)}]\), the event where the code for message \(i\) is jointly typical with \(Y^n\). The error \(\bar{\lambda}_1\) can then be expressed as:

\[\bar{\lambda}_1 = \text{Pr}(\varepsilon_1^c \cup \varepsilon_2 \cup \dots \cup \varepsilon_m)\]This is exactly equivalent what we have defined as an error for the jointly typical decoding. We then have the following bounds,

\[\begin{align} \bar{\lambda}_1 &\leq \text{Pr}(\varepsilon_1^c) + \sum_{i=2}^{2^{nR}} \text{Pr}(\varepsilon_i) &\text{(Union bound)}\\ &\leq \delta + \sum_{i=2}^{2^{nR}} 2^{-n(I(X;Y)-3\epsilon)} &\text{(Properties of joint typicality)}\\ &\leq \delta + 2^{-n(I(X;Y)-R-3\epsilon)} \end{align}\]Now, if \(R < I(X;Y) - 3\epsilon\), we can make \(\bar{\lambda}_1 \leq 2\delta\) for some large \(n\). Also note that \(\text{Pr}(\varepsilon_1^c) \leq \delta\) only hold for a large \(n\) too.

To get the actual proof, we replace \(Q\) with the capacity-achieving distribution \(\underset{Q \in P_X}{\text{argmax}}~I(Q,W)\). The last conclusion above becomes \(R < C^{(I)} - 3\epsilon\) implying \(P_e^{(n)} = \bar{\lambda}_1 \leq 2\delta\). Next, we have a fundamental lemma about the average of numbers:

Lemma 1: Consider a sequence of real numbers \(a_1,\dots, a_n\). If the average \(\bar{a} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n a_i \leq \gamma\), then there exists an \(a_i \leq \gamma\).

This lemma can be proven easily by contradiction. The implication of this is that previously we have shown that the average error \(P_e^{(n)} \leq 2\delta\) over all random codebook, then there must exist a codebook \(\mathcal{C}^*\) whose average error \(P_e^{(n)}(\mathcal{C}^*) \leq 2\delta\). It remains to bound the maximal error \(\lambda_\max(\mathcal{C}^*) = \underset{m\in \mathcal{M}}{\max}\lambda_m(\mathcal{C}^*)\), which is actually we need to show for the achievability of the rate \(R\).

Lemma 2: Consider a sequence of \(2n\) real numbers such that \(a_1\leq \dots \leq a_{2n}\) and its average \(\bar{a} \leq \nu\). It holds that \(a_n \leq 2\nu\).

Proof:

\[\begin{align} 2n\nu &\geq \sum_{i=1}^{2n} a_i = \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_i + \sum_{i=n+1}^{2n} a_i\\ &\geq \sum_{i=n+1}^{2n} a_i \\ &\geq \sum_{i=n+1}^{2n} a_n = n a_n \end{align}\]Using the lemma, we have a bound on the maximal error \(\lambda_\max(\mathcal{C}^*)\leq 4\delta\) by throwing away half of the codewords in \(\mathcal{C}^*\). However, by throwing away codewords we also lose the rate of communication, it is now \(R-\frac{1}{n}\) instead of \(R\). Indeed, the \(\frac{1}{n}\) would vanish for a large \(n\). Overall, this strategy of bounding the maximum is called the expurgation trick.

For a rate \(\tilde{R} < C^{(I)}\) and any \(\tilde{\epsilon}>0\), we can show that for \(n\) large enough there exists a rate-\(R\) (\(\tilde{R} < R\)) blocklength-\(n\) codebook where \(\lambda_\max \leq \tilde{\epsilon}\) by setting \(R=\frac{(\tilde{R}+C)}{2}\), \(\delta=\frac{\tilde{\epsilon}}{4}\), \(\epsilon < \frac{C^{(I)}-R}{3}\) and apply the proof above.